This post is more of a long-winded suggestion to read something else. That something else is very long, so it might take a bit of convincing. This series of articles, entitled the Anosognosic’s Dilemma and written by well-known documentarian Errol Morris, is one of the best things I’ve read on the internet (and the internet is obviously the best place to read things, right?). It’s long, but you should read it. There are many, many interesting parts. It’s largely about ‘unknown unknowns’; essentially: what you don’t even know you don’t know. I’ll talk about a couple interesting parts of this five part essay below. To keep you reading, some teasers: Part 1 is about a fascinating psychology study that more or less proved how ALL people (not just their mothers) think they’re slightly above average. Part 2 is about how one of the presidents of the United States probably wasn’t mentally competent for over a year (I promise this isn’t a long-form GW Bush joke)! Which one?! Read on…

First, what is now called the Dunning-Kruger effect. Pretty badass when you write a paper and they name the phenomenon after you. Since I’m trying to be all scientific on here, I’ll go ahead and do a mini-synopsis of the actual paper. It was published in 1999 by Cornell psychologist David Dunning and his graduate student Justin Kruger. The study was designed to quantify a fairly everyday phenomenon: the idea that the majority of people think they’re above average (for example, I am amongst the majority that thinks of himself as an above average driver; I’m probably not). Here’s a summary of the studies right from the paper:

“We explored these predictions in four studies. In each, we presented participants with tests that assessed their ability in a domain in which knowledge, wisdom, or savvy was crucial: humor (Study1), logical reasoning (Studies 2 and 4), and English grammar (Study3). We then asked participants to assess their ability and test performance.”

Obviously as I’ve talked about before test-taking is hardly an end-all-be-all, but as the authors are largely studying learned phenomenon like ‘knowledge’ and ‘wisdom’ we’re not having an IQ debate; more an assessment of how good people are within the specific realm of each study. And the subjects were dozens of Cornell University undergraduates, so we’re talking about a somewhat homogenous population of Ivy Leaguers that they’re divvying up into quartiles (obviously using the population at large might extend the absolute scores quite a bit, although the logic applies regardless). Study 1 compared the undergraduates’ assessment of the funniness of jokes to those of 7 professional comedians. Study 2 gave them 20 LSAT questions. Study 3 was a 20 question test on grammar. The 4th another logic test called the Wason selection test.

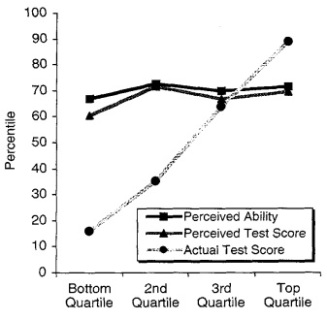

The nice thing about the paper is that even though there are 4 separate studies, all 4 graphs look almost identical. Here’s one:

(source: doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121)

This graph is hilarious! It’s the grammar one from Study 3 if you care. It tested 84 subjects. So, the average value you see in the bottom quartile is for the worst-performing 21 subjects. They tested out at the 15th percentile, so the average person in that group did better than only 15% of the entire group. The top 21 subjects answered better than 90% of the entire group. The actual data (grey line) has a nice slope up, meaning the test did a pretty good job of separating people.

The hilarious part is how uniform the participants’ perceptions are. All four groups, no matter how poorly or well (I almost said ‘bad’ or ‘good’—I probably belong in the bottom quartile) they actually did, on average thought they performed between 60-70%. They also perceived their overall ability to be around 60-70%. And as I said if you look at the other 3 graphs for the other 3 tests they’re all largely the same. In fact, for all 4 studies none of the 16 quartiles ever gave themselves a perceived score less than 50% (or greater than 75%). We all like to think we’re average (but usually only a little above average; most of us have some humility).

While the data is cleaner than I would have imagined, the basic principles of the study make sense to me. As humans we like to normalize ourselves to others, so sprinkle in a little confirmation bias and psychological optimism and you got a Dunning-Kruger stew going. I think it says a lot about us as a species though. Tying this back into the Errol Morris article that alerted me to this study, if you haven’t looked up what an anosognosic is yet, it’s someone with a psychological deficit in recognizing what he/she doesn’t understand. An extreme example is people that cannot move one of their arms but don’t realize it. You ask them to move their left arm, and they’ll pick it up with their right. You accuse them of this cheat, and they claim they’re not doing it. It seems unbelievable, but how our brain shapes our reality is not as objective as we like to think. And this is the ‘anosognosic’s dilemma’: you don’t know what you don’t even know! And as this paper by Kruger & Dunning shows, in this varied and complicated world of ours, we all probably know less than we think we do.

Now, if you made it this far, it’s probably only because you wanted to hear about our mysterious anosognosic president (or you skipped ahead. Ctrl-f is a great hotkey). I had never heard about this before from anywhere else, and frankly it just sounds like there wasn’t reporting back in the day like there is now for us to know what was going on. And this anosognosiac phenomenon likely shaped world history more than we’ll ever know. I make it sound like this president must have been from a while ago. But he was in office within the last century!

Directly borrowing from Errol’s article to further the build-up:

“. . . I waited up there until Doctor Grayson came, which was but a few minutes at most. A little after nine, I should say, Doctor Grayson attempted to walk right in, but the door was locked. He knocked quietly and, upon the door being opened, he entered. I continued to wait in the outer hall. In about ten minutes Doctor Grayson came out and with raised arms said, “My God, the President is paralyzed!”

Woodrow Wilson had a stroke on October 2, 1919. We have the day-to-day notes of his condition from his doctor, Admiral Cary T. Grayson. He suffered from complete paralysis of the left side of his body and a loss of vision in the left field in both eyes. He had difficulty swallowing and speaking from the left side due to paralysis in his throat/mouth. He also incessantly recited limericks to his doctors. He also denied there was anything wrong with him.

At the least read the 3rd part of this Errol Morris article to get the whole account. It’s unbelievable (but actually believable). Wilson’s anosognosia—not realizing he was not his true self—led to capricious behavior and the firing of many of his associates. Meanwhile anyone who spoke out about his potential disabilities was covered up. Meaning the leader of the most powerful nation in the world (even in 1919) might well have not been of sound mind for over two years of his presidency. And hardly anyone knew. This very well might have led to the dissolution of the League of Nations, which in turn might have promoted WWII. This is all speculation now, much like our speculation on how disabled Woodrow Wilson really was post-stroke. At the least, I’ve likely turned an unknown unknown for you into a known unknown; hopefully you can appreciate the intricacies of the anosognosia we all experience every day. Your brain does NOT give you an objective account of the real world.